Pinaceae – Pine Family

In 2024, this longleaf pine measured at 73 feet tall and had a diameter of 17 inches. Based on USDA Forest Service models, it will absorb approximately 1,506 lbs. of carbon over the next 20 years. Put simply, this tree will offset up to 6,098 car miles worth of carbon dioxide.

See all species on our Campus Tree Tour.

Introduction

For centuries, the longleaf pine has been valued for its cultural, economic, and ecological significance to the Southeastern United States. The tall, iconic tree is easily recognized by its fire-resistant reddish-brown bark, long green needles, and large cones. The longleaf pine provided humans with wood and turpentine, while its ecosystems support a rich diversity of native plants and animals. Despite population declines, ongoing restoration efforts aim to protect the endangered pine species and maintain these valuable habitats.

Physical Description

Life expectancy: Over 500 years

Height: 60 – 125 feet

Crown: 30 – 40 feet

Diameter: Up to 24 – 36 inches

Bark: Reddish brown, thick with plates that flake off as a defense to fire.

Leaves: Evergreen needles (8 to 18 inches long). The needles grow in a bundle, or fascicle, of 3 needles per bundle. Needles turn brown once they fall to the ground.

Twigs: Thick and stout.

Flowers: No flowers. Catkins (male cones) are produced in July while conelets (female cones) begin forming in August. The number of cones depends on annual weather conditions.

Cones: Large (6 to 8 inch) scaley cones that hold an average of 35 winged seeds that are wind dispersed during the fall. Cone production is infrequent, and they are produced every few years.

Key Identification Characteristics: reddish brown flakey bark, needles in fascicles of 3, large cones, thick twigs

Past and Present Uses

Indigenous tribes, such as the Louisiana Coushatta tribe, used the pine needles to skillfully weave baskets. Early settlers extensively used longleaf pine timber and resin for sawtimber, ship building, pulpwood, and poles. Its wood grows straight with limited defects, making it highly valuable, and its resin was used to produce turpentine for soap, candles, paint, printing, and medicine.

Currently, the longleaf pine’s role in the timber industry is limited since restoration efforts have become the primary focus. Yet, longleaf pine needles are commercially used as mulch for landscaping due to their slow decomposition rate and high nitrogen content. Needles from slash pines and loblolly pines are also used for this purpose. While turpentine is occasionally used as naval paints, it is more commonly used in spray paints and ceramic coatings.

Ecological Importance

Origin: Native to the United States

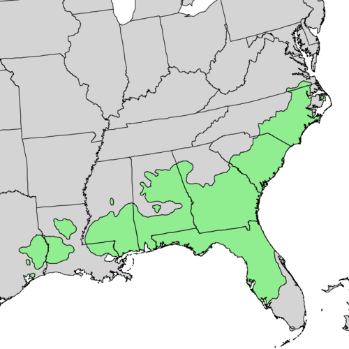

Native Range: Found in the Southeast U.S from Virginia to Florida and west to Texas (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Native range of Longleaf Pine. Photo credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Longleaf pine favors warm climates, growing in flatwoods and sandhill habitats that are regularly burned. Plant species associated with the longleaf pine vary depending on the frequency and severity of prescribed fires: frequent fires encourage the domination of grasses such as wiregrass; and less-frequent fires encourage other pines and hardwoods to encroach upon the longleaf pine habitat.

The longleaf pine was once a dominant species in the Southeast due to its fire resistance. When seedlings germinate, the plants enter a “grass stage” to develop an anchoring tap root, a thick stem, and long needles that protect the tree from fire as it matures. Populations began declining within the 20th century for various reasons such as disturbance from invasive wild hogs, poor logging practices, slow maturity of the grass stage, and fire suppression.

Recent initiatives have helped restore longleaf pine ecosystems as they are a foundational species that promotes biodiversity. About 68 different bird species, such as bobwhite quail and wild turkey, use longleaf pine forests for a food source or as a habitat. For example, old-growth pine stands provide the ideal habitat for endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers since they need older trunks to excavate cavities for their nests.

More Information

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ST469

References

Boyer, W. D. (n.d.). Longleaf Pine. Pinus palustris Mill. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/pinus/palustris.htm

Carey, J. H. (1992c). Pinus palustris. In: Fire Effects Information System. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/pinpal/all.html

Davis, S. (2023, February 22). The Legacy of Longleaf Pine. Dogwood Alliance. https://dogwoodalliance.org/2021/07/the-legacy-of-longleaf-pine/

i-Tree. (2006). Tree tools - calculate the benefits of trees!. i-Tree. https://www.itreetools.org/

Pinus palustris. North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox. (n.d.). https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/pinus-palustris/

Pinus palustris. Smithsonian Gardens. (2021). https://gardens.si.edu/collections/explore/object/ofeo-sg_2019-0145A#:~:text=Many%20Native%20American%20tribes%20used,still%20known%20for%20their%20skills

Turpentine. Delaware Health and Social Services. Division of Public Health. (n.d.). https://dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/files/turpentfaq.pdf